On September 3, 1939 Britain declared war on Germany. It was not unexpected, and New Zealanders learned of this final development when our Prime Minister advised us on radio, and said "Where Britain goes, we go".

And so began World War Two.

On 9 May, 1945 the world celebrated victory in Europe. VE Day was a great occasion - but there was still more work to do. Japan was yet to be defeated. It would take another three months before the world was at peace again. The worst conflict in human history officially ended on 15 August, 1945.

Outbreak of War

Ford New Zealand had been established just three years earlier. In that short time the company had faced great challenges - as outlined in the Ford in New Zealand book - and now we were at war! To his eternal credit, the Ford New Zealand managing director, George Jackson - remember that name for he is prominent in this story - was the first of our leaders of industry to offer their manufacturing plant to the war effort.

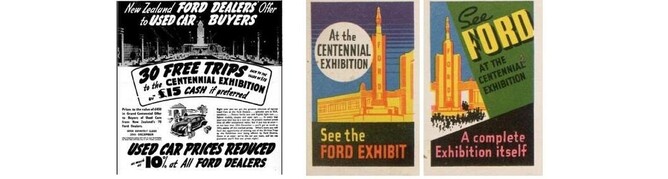

It was an offer that was immediately accepted. But first, a decision needed to be made about the forthcoming Centennial Exhibition.

1940 was the centennial of the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi - the founding of Aotearoa New Zealand. Great plans were in place, and the construction of the massive, purpose-built exhibition centre at Lyall Bay, Wellington was almost completed. Indeed, George Jackson was on the Centennial Exhibition organising committee, and he had committed to Ford New Zealand participation in the halls. The decision to proceed was celebrated and it opened on 8 November, 1939. Between then and 4 May, 1940 an incredible 2.6 million people went through the Exhibition turnstiles. More than a million of those visited the impressive Ford New Zealand exhibit - there is a four-page spread in the Ford in New Zealand book, including an image of the working model of the Seaview Ford factory in miniature! Whatever became of that model?

Meanwhile, as men began to enlist for the armed services, the Ford plant continued production. Upon the declaration of war, our government restricted the importation of new vehicles from North America for civilian use and, very quickly, production was under way of Canadian vehicles for the military. This included Ford V8 pick-up trucks to heavy Marmon-Herrington tank transporters and airfield crash tenders.

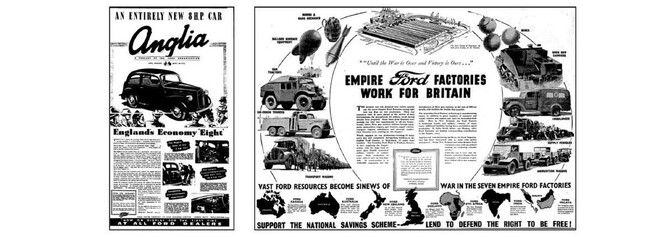

However, contrary to popular belief, civilian production was to continue for some types - for the time being, at least. Ford of England - much closer to the war, of course, than us here in New Zealand - continued production of the highly-successful 8 and 10-horsepower cars at Dagenham for export. The idea was to continue such sales to earn Britain valuable overseas currency, to help pay for the war. But once Hitler's armies had invaded France, and now occupied all of western Europe and had turned their attention to Britain, Dagenham switched to dedicated war production only. The last of the civilian Fords from Britain arrived here about August or September - but, because of the uncertainties brought about by the war, there was now little appetite for new cars.

The image below shows, at left, a typical New Zealand newspaper advertisement from July, 1940. The Ford 8 had become the Ford Anglia! A few months later, Ford New Zealand advertising announced that all their factories throughout the British Empire were involved in production of vehicles, machinery and armaments for the war, and Herr Hitler had better look out.

War Production

The Ford in New Zealand book has a 28-page chapter which describes in detail the war years, complete with production figures. However, this blog story is a great opportunity to clear up the mistaken belief that the New Zealand-made universal carriers, or bren gun carriers, were made by General Motors New Zealand!

One of the great aspects of industrial production during World War Two is that competitive rivalries were set aside - everyone worked together for the common goal of winning the war. Amongst the military vehicles produced, perhaps the universal carriers were a best example of that collaboration: the New Zealand Railway Workshops in Woburn, Lower Hutt made the bodies and chassis; Ford New Zealand contributed the Ford V8 motors (100 horsepower, not the English 60 hp version so often suggested!) and transmission, including the rear axle. Hundreds of other parts, many made to within one-thousandth of an inch, were produced by various manufacturers and workshops throughout New Zealand. General Motors' role was to assemble the universal carrier, at the premises in Petone.

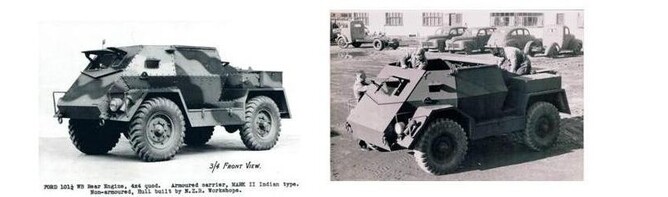

Such arrangements were commonplace during the war - another example is the Ford-made "Rear-Engine Quads" (see photos below). Like most military vehicles, these were built to exacting military specifications. The "Quads" (so named for their four-wheel drive systems) had their chassis assembled on the Ford New Zealand production lines, after which they were taken to the Railway Workshops where the bodies were made and fitted.

In the background of the above right photo, taken at the Ford plant in Seaview, workers are completing details on a Quad. In the background are three of the ten 1942 Ford V8 staff cars, imported from Ford of Canada. It is said that the 1942 Ford V8s are the rarest of all Ford production cars, as they were made for only a very short time before America entered the war. Two of those ten cars are known to have survived, and there is a colour photo of one of the two in the Ford in New Zealand book. The photo below, from the New Zealand Air Force Museum, shows one of those 1942 V8s in service, parked behind another military vehicle, a 1939 Ford V8 De Luxe staff car, likely impressed into service.

Another aspect of the military vehicle work undertaken at the Ford factory was the Jeep recovery program. Rather that cast them aside, damaged Jeeps were shipped from the Pacific warzone to Wellington, to be repaired and reconditioned at the Ford plant. The Jeeps were taken completely apart, then re-assembled on the lines using new or serviceable parts - then returned to the warzone. More than 1,100 Jeeps were recovered in this way - it was quicker and cheaper than replacing damaged or broken Jeeps with new units from the American mainland!

Women and Munitions

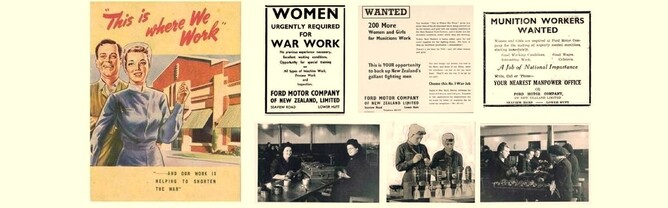

In July, 1940 Ford New Zealand began a wartime activity for which it would become famous. The work was to assemble and hand-fill grenades - 800 a day at the start, on frictionless assembly lines. This was just the beginning for Ford New Zealand, the company that was to become New Zealand's largest munitions manufacturer!

With thousands of men having joined up to fight, for the first time in New Zealand women would now be employed in a factory. Whilst most of the heavy work related to building military vehicles continued to be handled by men, the making of munitions and explosives would be undertaken by women. All were volunteers - and all knew of the dangers involved.

Munitions manufacturing advanced to bombs and mortar bombs. When the military needed supplies of Fuze 119 - the military name for the nose cap of 25-pounder shells - the munitions work at Ford expanded again. Preparing these fuzes was a delicate operation and, at its peak, 4,000 fuzes a day were being completed, by a workforce of 490, mostly women. The work was also well suited for blind people, who could feel their way around the such mechanisms with more apparent safety those who with full vision.

It was not just the risk of an explosion within the Ford building that workers needed to fear, the Ford building was a likely target for an air raid. With Japan's entry into the war and their southern push towards Australia and New Zealand, the prospect of a Japanese attack was realistic. When the Defence Department painted to roof of the Ford plant to help camouflage it against an air attack, the Japanese propaganda broadcaster Tokyo Rose warned us that "our pilots can still see the Ford factory and will be coming soon to bomb you".

On her surprise visit to New Zealand in August, 1943 the American First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt paid a visit to the women working in the Ford factory. But all this is covered in the Ford book, as is the production statistics.

Advertisements calling for women workers at the Ford factory were commonplace at the time. The booklet (above left) was an effort by the Defence Department to recruit more workers for munitions production at the Ford plant.

The End of the War

As said right at the beginning of this article, the war eventually came to an end. Japan had surrendered. At the Ford factory, the job was done.

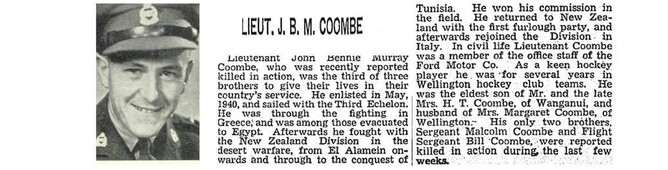

But, at what cost? Britain was almost bankrupt from it. And the cost in human life was extraordinary. That includes workers who, in the call to arms, had voluntarily left their employment with Ford or out in the Ford dealerships, and joined the fight. Lest we forget that some paid the ultimate price, including our example Ford worker below, John Coombe, who never came home. Please make sure you read the tragic accompanying news story....

George Jackson - remember, he was the Managing Director of Ford New Zealand during this time - became heavily involved in New Zealand's war effort,. He was posted by the government to a role leading the direction and co-ordination of all activities of Government Departments relating to production and supply, and with the promotion through New Zealand manufacturers of maximum output of munitions and essential goods. Some say he should have been knighted for his work. Announced in the 1946 New Year's Honours list, George Jackson was awarded the OBE.

At the same time, two other workers from the Ford plant were also recognised. Once was Joyce Werner and, in spite of efforts of this author, nothing is known of her work or where she went after the war.

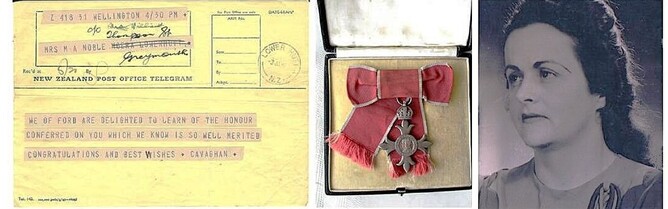

The third was an MBE awarded to Mrs Maisie Noble. It is understood she earned her award not just for the valuable munitions work she undertook, but in the care she showed towards some of the youngest and most vulnerable members of our society at that time. These were the young women and girls, some from remote parts of the country, exposed to city perils and the most dangerous work imaginable. The author was contacted by her son, John, years ago and it has been an absolute privilege to learn about Maisie (see below) and, in spite of never meeting her, to feel very close to her.

The war had ended. But the suffering would endure.

(Above: telegram from Ford to Maisie Noble, advising her of her award; her MBM is a prize possession of her son John; studio photo of Maise Noble.)